What is Cervical Cancer?

Cervical cancer occurs when abnormal cells in the lining of the cervix grow in an uncontrolled way and eventually form a tumor. It has been found to be most common in women in their early 30s. Squamous cell cancer and adenocarcinoma are the two most common types of cervical cancer. Squamous cell carcinoma accounts for 70-80% of all cases and involves the skin-like-cells of the surface of the cervix. Adenocarcinomas occur in the glandular tissue inside of the cervix, that are responsible for producing mucus. One of the main causes of cervical cancer is a persistent infection of human papillomavirus (HPV)[1]. Vaccinations against HPV have proven to offer protective benefits in the reduction of cervical cancer [10].

Cervical Cancer Statistics in a Preventable Disease

Cervical cancer is the fourth most frequent cancer in women worldwide [2]. Data from GLOBOCAN estimated cervical cancer accounted for 604,000 new cases and 342,000 deaths in 2020 with 90% of these occurring in low-middle income countries [3]. Increasing screening and prevention are key components to reducing these figures [4]. Pap smears can catch the disease at the pre-cancerous stage[18]. Early diagnosis and prompt treatment make cervical cancer a treatable disease [2]. In May 2018, the World Health Organization (WHO) made a call for action to eliminate cervical cancer as a public health problem in all countries [5,6].

The consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic have also impacted the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of cervical cancer globally. A literature review found a significant decrease in vaccinations, pap smears, and early diagnosis in various countries. During 2020 it was reported in Brazil that there was a 13.5% increase in patients diagnosed with advanced stage disease compared to the pre-pandemic period. A survey of 70 gynecologic oncologists in Turkey found that 57.1% of respondents changed their approach to cervical cancer management including shifting to hypofractionated radiotherapy, instead of standard radiotherapy, to reduce the number of hospital visits [10].

Treatment guidelines

Post-operative Radiation Therapy

Cervical cancer treatment can include a combination of surgery, chemotherapy and radiation therapy depending on the size, type, and location of the tumor as well as a person’s overall health. There is strong evidence supporting the use of radiation therapy with or without chemotherapy in both definitive and postoperative settings. In 2020, the American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) created a task force to provide recommendations for the appropriate techniques of radiation therapy in the treatment of non-metastatic cervical cancer[11]. The guidelines recommend post-operative radiation therapy for patients with intermediate risk factors and chemoradiation for those with high risk factors.

In the last two decades, there have been notable advances in surgical procedures, external radiation therapy techniques, brachytherapy and chemotherapy regimens[11]. Radiation is an integral part of the management of locally advanced disease whether as an adjuvant treatment after surgery or as a primary curative treatment[11]

Image-guided Radiation Therapy

Intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) is the recommended radiation therapy technique for external beam radiation therapy (EBRT) for all women to allow dose escalation and reduce acute and late toxicity. IMRT minimizes dose to the bladder, rectum, bowel, and bone marrow which can potentially reduce side effects and allow patients to experience a better quality of life after treatment. Management of tumor motion with the use of image guidance is of the upmost importance in IMRT to ensure treatment accuracy. EBRT is usually followed by an intracavity brachytherapy boost to the primary site, which has been shown to be an essential part of definitive management. Using image guided brachytherapy (IGBT) serves to deliver a high radiation dose internally to the cervix while helping minimize the dose to the surrounding anatomy[11].

ESTRO and ASTRO Guidelines

The European Society of Gynecological Oncology, European Society of Radiotherapy and Oncology, and the European Society of Pathology (ESGO-ESTRO-ESP) published guidelines for the treatment of cervical cancer in 2018[12], which closely align with the ASTRO 2020 guidelines. These guidelines state that MRI image-guided brachytherapy is the preferable choice, recommended as an integral component of definitive radiation therapy as it has consistently demonstrated improved outcomes. A large study called the EMBRACE study provided strong evidence of long-term local control in locally advanced cervical cancer using chemoradiotherapy and MRI-based image-guided adaptive brachytherapy (IGABT)[13].

Challenges with Brachytherapy

In the real-world there has been declining use of brachytherapy. For some countries like Germany it can be difficult to find adequate brachytherapy with high tech brachytherapy equipment that meet the requirements of GEC-ESTRO recommendations, making access limited[15]. Another study revealed a decline in brachytherapy utilization in the U.S that was strongly influenced by federal reimbursement policies adopting the use of IMRT boost as an alternative to brachytherapy for cervical cancer.

Brachytherapy is technically demanding and resource intensive, therefore it became more feasible to choose IMRT as an alternative than referring to another facility[17]. Additional challenges include unfavorable patient anatomy, difficulties in placing a Smit sleeve or pre-existing medical conditions that preclude the use of a brachytherapy boost, the presence of asymmetric tumors where a satisfying dose coverage cannot be achieved with the brachytherapy equipment available, and patient refusal of the procedure[15]. For these situations, a targeted external stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) boost can be considered[11].

What is the alternative option for patients?

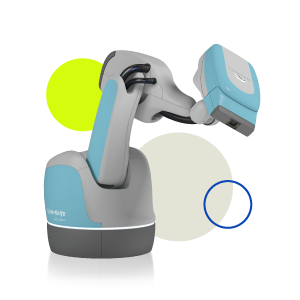

Several studies have examined the safety and efficacy of delivering an SBRT boost with the CyberKnife® System to the cervix after EBRT in patients unable to receive treatment with brachytherapy. The CyberKnife System has been shown to allow more precise targeting and delivery of radiation to the cervix compared to conventional linac-based radiation. This allows dose escalation to the cervix that demonstrates a comparable dose to a brachytherapy boost[14].

CyberKnife SBRT emulates brachytherapy by having multiple non-coplanar beams intersecting the cervix, delivering a high therapeutic dose while minimizing dose to normal anatomy. It provides steep dose gradients, offering excellent coverage of complex target volumes[15], with the added advantage of performing real-time motion tracking where the dynamic robotic delivery automatically changes the position of the linear accelerator to correct for rotational and translational movement of the patient and the cervix during treatment. This automatic motion correction capability is imperative to ensure the accurate delivery of high-dose radiation[14].

CyberKnife System studies have demonstrated excellent local control with no increase in toxicities after EBRT [15]. While direct comparisons aren’t possible, the overall survival rates achieved using CyberKnife SBRT boost have been similar to those published in the brachytherapy EMBRACE trial[15]. Another study compared CyberKnife and brachytherapy plans finding that the Cyberknife SBRT boost could result in significantly better target coverage, organ at risk (OARs) sparing and radiobiological effects compared to the brachytherapy plan[16].

The CyberKnife System can provide an alternative option for cervical cancer patients

Learn more

References

1. About cervical cancer | Cancer Research UK

2. Cervical cancer (who.int)

3. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics

2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in

185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021 May;71(3):209-249. doi:

10.3322/caac.21660. Epub 2021 Feb 4. PMID: 33538338.

4. January is Cervical Cancer Awareness Month | The AACR

5. Rajaram S, Gupta B. Screening for cervical cancer: Choices & dilemmas. Indian J Med Res. 2021 Aug;154(2):210-220. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_857_20. PMID: 34854432; PMCID: PMC9131755.

6.https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240014107

7. Mehrotra R, Yadav K. Cervical Cancer: Formulation and Implementation of Govt of India Guidelines for Screening and Management. Indian J Gynecol Oncol. 2022;20(1):4.

doi: 10.1007/s40944-021-00602-z. Epub 2021 Dec 27. PMID: 34977333; PMCID:

PMC8711687.

8. Bhatla N, Meena J, Kumari S, Banerjee D, Singh P, Natarajan J. Cervical Cancer Prevention Efforts in India. Indian J Gynecol Oncol. 2021;19(3):41. doi: 10.1007/s40944-021-00526-8. Epub 2021 Jun 2. PMID:

34095455; PMCID: PMC8170054.

9. SinghMP, Chauhan AS, Rai B, Ghoshal S, Prinja S. Cost of Treatment for Cervical

Cancer in India. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2020 Sep 1;21(9):2639-2646. doi:

10.31557/APJCP.2020.21.9.2639. PMID: 32986363; PMCID: PMC7779435.

10. Ferrara P, Dellagiacoma G, Alberti F, GentileL, Bertuccio P, Odone A. Prevention, diagnosis and treatment of cervicalcancer: A systematic review of the impact of COVID-19 on patient care. Prev

Med. 2022 Nov;164:107264. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2022.107264. Epub 2022 Sep 20.

PMID: 36150446; PMCID: PMC9487163.

11. Chino J, Annunziata CM, Beriwal S, Bradfield L,Erickson BA, Fields EC, Fitch K, Harkenrider MM, Holschneider CH, Kamrava M,Leung E, Lin LL, Mayadev JS, Morcos M, Nwachukwu C, Petereit D, Viswanathan AN.Radiation Therapy for Cervical Cancer: Executive Summary of an ASTRO Clinical

Practice Guideline. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2020 Jul-Aug;10(4):220-234. doi:

10.1016/j.prro.2020.04.002. Epub 2020 May 18. PMID: 32473857; PMCID:

PMC8802172.

12. Cibula D, Pötter R, Planchamp F, etal The European Society of Gynaecological Oncology/European Society forRadiotherapy and Oncology/European Society of Pathology Guidelines for theManagement of Patients With Cervical Cancer International Journal ofGynecologic Cancer 2018;28:641-655.

13. Pötter R, Tanderup K, Schmid MP,Jürgenliemk-Schulz I, Haie-Meder C, Fokdal LU, Sturdza AE, Hoskin P,Mahantshetty U, Segedin B, Bruheim K, Huang F, Rai B, Cooper R, van derSteen-Banasik E, Van Limbergen E, Pieters BR, Tan LT, Nout RA, De Leeuw AAC, Ristl R, Petric P, Nesvacil N, Kirchheiner K, Kirisits C, Lindegaard JC; EMBRACE Collaborative Group. MRI-guided adaptive brachytherapy in locally

advanced cervical cancer (EMBRACE-I): a multicentre prospective cohort study.

Lancet Oncol. 2021 Apr;22(4):538-547. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30753-1. PMID:

33794207.

14. Haas JA, Witten MR, Clancey O, Episcopia K,Accordino D, Chalas E. CyberKnife Boost for Patients with Cervical Cancer Unable to Undergo Brachytherapy. Front Oncol. 2012 Mar 21;2:25. doi:

10.3389/fonc.2012.00025. PMID: 22655266; PMCID: PMC3356152.

15. Morgenthaler J, Köhler C, Budach V, Sehouli J, Stromberger C, Besserer A, Trommer M, Baues C, Marnitz S. Long-term results of robotic radiosurgery for non brachytherapy patients with cervical cancer. Strahlenther Onkol. 2021 Jun;197(6):474-486. doi: 10.1007/s00066-020-01685-x.

Epub 2020 Sep 24. PMID: 32970164; PMCID: PMC8154829.

16. Gao J, Xu B, Lin Y, Xu Z, Huang M, Li X, Wu X, Chen Y. Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy Boost with the CyberKnife for Locally Advanced Cervical Cancer: Dosimetric Analysis and Potential

Clinical Benefits. Cancers (Basel). 2022 Oct 21;14(20):5166. doi: 10.3390/cancers14205166.

PMID: 36291951; PMCID: PMC9600637.

17. Han K, Milosevic M, Fyles A, Pintilie M, Viswanathan AN. Trends in the utilization of brachytherapy in cervical cancer in the United States. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013 Sep 1;87(1):111-9.

doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.05.033. Epub 2013 Jul 9. PMID: 23849695.

18.https://www.aacr.org/patients-caregivers/awareness-months/cervical-cancer-awareness-month/

19.https://www.cancer.gov/news-events/cancer-currents-blog/2020/hpv-vaccine-prevents-cervical-cancer-sweden study#:~:text=In%20the%20study%20of%20nearly,who%20had%20not%20been%20vaccinated