Around 2,300 children and adolescents are diagnosed with cancer every year in France..1 Paediatric cancers include a multitude of rare diseases whose treatment requires a multidisciplinary and personalized approach tailored to each young patient. Radiotherapy is one of the pillars of cancer treatment. It is estimated that around one in three children with cancer will undergo radiotherapy as part of their treatment.2 Due to its highly technical nature, this treatment option can be anxiety-inducing for young patients and also for their families. A number of initiatives are currently in use to help children deal with their anxiety, such as the use of Lego models of the radiotherapy room during consultations and virtual reality headsets during sessions.3-5 The Miroki humanoid robot has been integrated into the Montpellier Cancer Institute’s paediatric radiotherapy department.6 The aim of this integration is to accompany young patients throughout their treatment journey and provide them with essential emotional support in order to improve the quality of their treatment. During the “Artificial Intelligence for Radiation Oncology” course organized by UNICANCER in January 2026, we spoke to Dr. Julien Welmant, a radiation oncologist and the originator of this project, in order to bring some insight on the subject.

Could you tell us a bit about your work and where your passion for robots comes from?

I am a radiation oncologist at the Montpellier Cancer Institute, where I treat children from ages 3 to 25. I’m the geek of the team, the person they call when the mouse isn’t working or when the software won’t install! I play video games and teach my daughter how to play them. And I’ve loved robots ever since I was little. What’s appealing to me is the technology that can be useful for people.

Can you tell us a little more specifically about what radiotherapy treatment for children involves?

In particular, children have to be on their own during paediatric radiotherapy sessions in a dedicated room, called a bunker. And in addition, they must not move. This is not the case during the rest of the treatment process where parents are allowed to be present: the mother and/or father can accompany the child to the operating theatre for surgery or be in the room during chemotherapy sessions or scans, for example, as long as they wear an apron to protect themselves from radiation. But this is not possible during radiotherapy treatments. We have to explain to children that they need to be alone in the bunker to be treated by a huge machine, on top of everything they are going through: their pain, nausea, chemotherapy, surgery, etc. While adults suffering from cancer also have to deal with this harsh reality, children in this situation find it very difficult to cope with.

Who is Miroki? And what does it do?

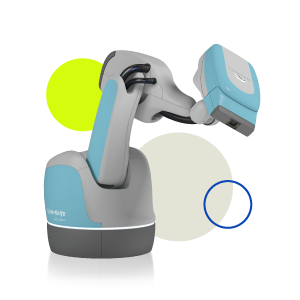

The name Miroki comes from the Japanese words miru, which means ‘to see’, and hoki which means “others”. So, Miroki means “one who sees others”. The idea is: “I am here for others”. Basically, the story places Miroki in a universe containing entities whose purpose is to bring well-being. These entities pass through a specific portal and their spirits can then incarnate in a robotic suit to help humans through it. So Miroki is much more than a robot or a toy. There is a whole story behind it, with a universe that children discover over time. Of course, it is not real, but it allows us to explain to children that the robot can break down, be replaced, be transferred to a tablet, and so on.

Initially, Miroki was developed to be present in social environments and remain in the background. It was supposed to push objects and carry things but, above all, not appear in the foreground. That’s why it didn’t need to talk. It just needed to be visible. It has a whole range of gestures and non-verbal communication: its ears move, it can blink its eyes slightly, and it is a bright orange colour that is easy to see. We make use of these characteristics when it is in the radiotherapy room, a place where we don’t want any interaction, because the child must not move even a fraction of an inch. Miroki just has to show that it is here. Even without speaking, the child knows they are not alone because they can sense its presence.

With the arrival of ChatGPT-type language models, it became possible to give Miroki a voice and make it speak using artificial intelligence. This now allows us to create interactions and real dialogues,, as well as various scenarios to further engage the child in their treatment. Today, we can have a conversation with Miroki, almost as if it were human.

At which step of the treatment process is Miroki introduced to children?

Miroki is present from the very beginning so that, by the time of the radiotherapy sessions, the child feels accompanied and no longer feels alone.

Where did the idea of developing Miroki come from?

The idea of developing Miroki came as a result of a problem I experienced several years ago with a young five-year-old patient called Charline.

It was probably the most difficult paediatric treatment of my career: she had to undergo three radiation treatments lasting a total of 30 minutes every day. Charline cried for an hour and a quarter every day for two and a half months. It was awful for her, awful for her parents, awful for the healthcare team, and particularly difficult for me, as the only way to calm Charline down at the end of that hour and a quarter was for me to go into the bunker and be the bad guy. It was the only solution. We had tried everything. The only thing that worked was when I went see her and said, “Right, Charline, it’s time to go”. So I said to myself, “I need to come up with something!”

There are things we can offer during radiotherapy: distractions, screens, music, that sort of thing, but they’re just distractions, there’s no comforting presence. And then one day, while I was in Japan and walking in the rain, I went into a shop where there was a robot that came up to me with a big smile and handed me a towel. I thought to myself, “It’s just a tin can, but I wasn’t feeling good and it smiled at me. It offered me a towel when I was soaking wet. I needed that towel and it made me feel better!”

I realised then that there are robots made to go places where humans cannot, like Mars or inside nuclear power plants, and others like this one that can greet you with a smile and make you feel better. Why not combine the two: a robot that can go to places we cannot go and that can also make you smile?

After taking robotics classes and approaching the Montpellier Laboratory of Computer Science, Robotics and Microelectronics (LIRMM), I finally contacted the CEO of a company that was developing ‘Miroki’, a cute logistics robot. It didn’t look anything like it does today. It was simply a very sleek, all-white prototype that didn’t talk. I suggested transforming this prototype into a robot that would be useful for my practice. They agreed immediately as the project gave purpose to their technology. And that’s how the idea of developing Miroki came about.

Does Miroki meet your expectations today?

We’ve seen the before and after with the robot! It has transformed the radiotherapy experience. Both children and parents come in more relaxed, and the caregivers can feel the difference!

Today, the Integrated Cancer Research Centre (SIRIC) allows us to draw on various transdisciplinary approaches, beyond cancer treatment, such as the humanities and social sciences. We are supported by psychologists to help us assess the degree of attachment between the machine and the child, by anthropologists to understand the extent to which Miroki can be perceived as a caregiver, and by sociologists to look at the societal model in which a humanoid robot plays a role in a hospital setting.

We realise that we can use Miroki in many areas of oncology, such as prevention. The Epidaure Centre in Montpellier welcomes nearly 5,000 children a year to talk about prevention, cancer, smoking, nutrition, and sun exposure, etc. In this context, Miroki could be a very good intermediary for prevention, distributing toys, goodies, information, etc. within the institute. We are considering investing in a second robot for this purpose.

In terms of supportive care, Miroki might be of use in nursing homes, with the aim of helping older people to perform exercises guided by a robot. In fact, we have found that when this type of motivation is provided by something other than a human being, in the form of a game, it is much easier. We know that humans have learned through stories and games. By providing a story and a game, the robot encourages physical exercise where a person might find it a little more difficult.

How many children have already received Miroki’s support?

Fifteen children have seen the robot at various stages, split into three age brackets: from four to seven, seven to 12, and over 12 years of age. In the case of the four to seven-year-olds, interaction is very much like a story. There isn’t much two-way communication; the child listens and the robot tells a story. From seven to 12 years of age, imagination is at its peak. There is real interaction at this stage. Children can go well into the story with Miroki.

During consultations, I always ask what children like because the robot is able to memorise it. So, if a child likes dinosaurs, the robot is able to talk about dinosaurs for hours on end. In the case of the over-twelves – the ‘TikTok generation’ – they are harder to engage. The robot needs to interact very quickly, and this is an area where we have some improvement to do. The robot’s latency is currently one to two seconds, which is a little slow for a natural conversation. This is a technological gap that we will soon remedy.

How did the healthcare teams take to Miroki?

At first, unsurprisingly, there was some reluctance to change and fear of being replaced. But they were quick to grasp the robot’s appeal: it could go places that humans cannot. Fear of replacement was then replaced by fear of mental overload, the idea of having to integrate a new tool that might make their work more difficult. However, the healthcare teams gradually realised that this was not the case, as the robot, being increasingly autonomous, is able to absorb part of the mental burden of treatment without ever passing it on. On the contrary, it reduces the overall burden on healthcare teams. Today, the robot is fully integrated, roaming around the ward, and everyone says, “Hello, Miroki, how are you?” as if it had always been there.

Will Miroki be deployed in other hospitals?

The ambition of the project is that one day all children in the world who need radiotherapy treatment will be able to benefit from a robot as part of their care!

Today, Miroki meets almost all of our expectations. However, we do need to improve its autonomy. This is because we still need a human to operate the robot in 40-50% of cases. We are currently working on a very minimalist interface that would allow radiotherapy technicians to use the robot for three to four functions, such as asking it to tell the child to “stay still”. But for everything else, it would be completely autonomous.

Finally, we need to raise awareness of the project and explain what Miroki is for. Even though we believe that it brings benefits, we will have to prove it. So, we are going to undertake a clinical study to assess the reduction in anxiety brought about through the use of this robot. We need scientific data to take Miroki beyond the simple concept of a toy.

To conclude, what message would you like to convey to people reading this blog?

There are two messages I would like to convey. The first is: “Research is always advancing, both in the field of pure treatments and in the field of healthcare experience.” The latter field will evolve over the next few years. My second message is: “When you have a dream, don’t give up on it! ” Even if people tell you it’s rubbish, even if they tell you it will never work. When you believe in something, you have to see it through to the end! The proof is that this project took two years. There were many hurdles, many obstacles, many difficulties, a lot of resistance, etc. Yet today, the project has become a reality. Today, all our children are treated with Miroki by their side. If at any one of those moments we had stopped and said it was too complicated, Miroki would never have seen the light of day.

Bibliography

- Panorama des cancers 2025 – édition spéciale 20 ans. INCa, latest consultation 16/01/2026.

- La radiothérapie. Société Française de lutte contre les Cancers et les leucémies de l’Enfant et de l’adolescent, last consulted 16/01/2026.

- Une salle de radiothérapie recréée en Lego pour lutter contre l’anxiété des enfants atteints d’un cancer. France 3 régions, last consulted 16/01/2026.

- La réalité virtuelle, un allié contre la peur des traitements cancéreux chez mon fils, casque VR, last consulted 16/01/2026.

- REalité Virtuelle pour l’Enfant en Radiothérapie. Centre Antoine Lacassagne, last consulted 16/01/2026.

- Miroki, le robot compagnon en radiothérapie pédiatrique. ICM, last consulted 16/01/2026.